Congratulations! You’ve made it to the end of week 1, or you’re only hours away from it starting. You have prepared your lecture, and you have rehearsed your seminar or tutorial lesson plan. You’re primed to be enthusiastic and passionate about your law or legal studies subject (like we talked about here). Great job! But what if I told you, though, that now might be a good time to think about the end of the semester and student evaluations? Have you thought about their expectations? Here are 5 steps for managing expectations in your law school classroom.

Getting ahead of student evaluations

At the end of the semester, Twitter comes alive with threads by college and university teachers about student evaluations – the good and the bad. A big part of those threads is teachers’ disappointment with both student comments. And lots of teachers worry about the discussion they expect to have with their Dean about law student (dis)satisfaction.

There is considerable debate over the utility of student evaluations as a performance assessment or management tool. The highly questionable (or just out-and-out objectionable and demeaning) content of free, online evaluation sites like ‘Rate my Professor’ further devalue student feedback.

Where they are completed honestly and sensibly, evaluation comments tend to fall into common categories. Usually, there are comments about assessment preparation, assessment tasks and feedback. There are often comments about what was taught (syllabus ) or how it was taught (curriculum ). And there is usually something about individual teaching style.

By the time the comments appear, it’s generally too late to do anything about a lot of them. Assessment tasks were locked in with the faculty board months or even years ahead. And lectures are ‘done and dusted’.

If only I’d known …

Of course, a lot of the feedback would have been valuable to have early on. Some of the comments might even explain why law students were really engaged. They might also explain why they performed poorly or didn’t turn up at other times. It might have had nothing to do with you at all! But it will also tell you about things that you might have been able to do or stop doing if you had known earlier.

So, what can we do to address law student evaluation comments before students even write them?

There are things that law students must do to succeed in law school. And law teachers have seen enough law students not do those things and perform poorly. When we talk about managing expectations in your law school classroom, we picture the traditional ‘expectations’ lecture. The wagging finger type, ‘thou shalt’ imposition of rules with which law students shall comply. But they’re not ‘expectations’; they’re rules.

Setting expectations

At the beginning of every semester, in the very first tutorial, I facilitate a discussion about expectations. That includes things that law students should do to succeed. But it also includes asking law students’ what their expectations of the unit are, what their expectations of each other are, and what their expectations of me are.

The idea of writing’ classroom rules’ together in elementary/primary school and even in secondary school is widespread. There are lots of books, articles and blog posts about classroom agreements by school teachers. The International Baccalaureate’s Primary Years Program mandates what they refer to as an ‘Essential Agreement’. Edna Sackson over at What Ed Said has a concise explanation of why:

Every working group (teachers or students) starts off by creating an ‘essential agreement’. In the classroom, this means that, rather than teachers imposing rules, everyone works collaboratively to establish an agreement of how the class will function.

I’ve always wondered why, moving from primary teaching to law school, law teachers don’t do the same thing. Especially when they’re subject to a much more explicit student evaluation process. It might be the idea that the Pearce Committee’s report on Australian legal education, for example, referred to: law students don’t know what they don’t know. That is, they can’t direct the syllabus and curriculum themselves.

I also wonder whether it might be a concern about making ourselves immediately visible in the teaching process. Or, in an Australian context, relying on the ‘strict legal formalism’ of the material to separate us from it. That is, the law is the law, and our role is merely to transmit it.

Why bother? Can’t I just get on with it?

Setting expectations before you start teaching can have some huge advantages for law students and law teachers.

If you have read the page about this blog and my teaching philosophy, I am passionately (wow, there’s a scary word for a lawyer) believe that knowledge and understanding are co-constructed. As law teachers, we facilitate the process. Law students are active partners in that process, not empty vessels passively receiving information. Formally acknowledging that role is an essential reminder for law teachers and our students. This leads me to the next point …

One of the finger-wagging, rules-type expectations that law teachers often cite is the need to ‘do the reading’. But acknowledging the active role of law students means they will independently set that expectation for themselves and each other. It’s not uncommon for law students to talk about the need for participation and sharing opinions. They usually go on and point out that everyone needs to know what they are talking about. So everyone has to do some preparation.

This might appear a little touchy-feely, but there is also some empirical evidence to support the process as well. In the late 1970s, psychologist Richard L. Oliver began to question the dominant effect that independent expectations were thought to have on consumer satisfaction. Psychologists found that expectations could be negotiated before consumers’ experience.

The research obviously had immediate implications for cars, whitegoods or restaurant reviews. But it can also help us think about law teachers’ initial discussions with their students. If law students’ expectations are explicit, we know what they are and can work to them. Alternatively, where they are beyond what’s achievable, you can explain why that can’t or won’t happen.

Five steps for managing expectations in your law school classroom

Step one: The icebreaker

In the first tutorial, I ask law students to participate in the usual ‘icebreaker’. Most icebreakers are cringe-worthy and just fill time. However, rather than the ‘two truths and a lie’ or whatever the activity du jour might be, I ask them to introduce themselves to another law student and ask that student two questions: ‘What are your expectations of the convenor?’ and ‘What are your expectations of your peers?’. I then get each student to introduce their partner. Getting them to ask someone else, and report what they heard, removes some of the tension from the exercise. It can be a bit confronting to say ‘I want you to …’, but ‘They want you to …’ means less risk of personal embarrassment. And it’s good advocacy training to put a position on behalf of someone else.

Step 2: Capture everything

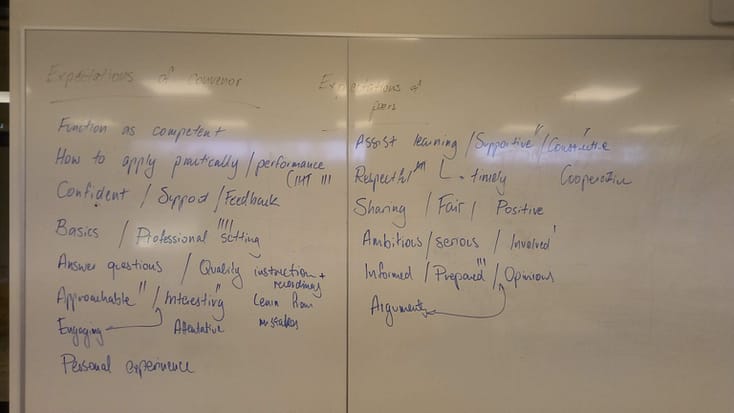

I capture all the suggestions on a whiteboard. Don’t reject or edit anything! Refusing to put something up or editing something looks like you’re being a little dishonest about the process or changing it on the run.

Step 3: Reading the terms and conditions

Once you have captured it, you can start working through the expectations. You can accept them, group them into ‘like’ expectations. For example, ‘approachable’, ‘helpful’ and ‘supportive’ might all be trying to say the same thing, depending on the context. Because you opened the discussion and you’re engaging, so long as you explain your concern reasonably, students are prepared to engage with you, to ask more questions or put alternatives.

Once the review is complete, I ask students to confirm that they are comfortable with what’s there. It’s not uncommon for a student to ask that something is clarified or added. They might even suggest that what they were trying to say can be grouped with something else.

Step 4: Record it

I then take a photograph of the whiteboard. It’s more manageable than trying to write it down. I turn it into a word cloud. Word clouds are a good way of what’s important. Where an expectation appears several times, the software that creates the cloud will make it larger or bolder. And it highlights the priority for you and the students of some expectations.

Step 5: Revisit it (often)

But for it to be effective, you can’t let the list get stale. Put it somewhere prominently (I usually put it on the front of the unit learning site page). Refer to it throughout the semester.

This is, of course, only one way to do it. There are many ways to have this discussion and record its outcomes.

Do you think this might be useful in managing expectations in your law school classroom?

2 Comments on “5 steps for managing expectations in your law school classroom”